Hello all, and welcome back to my blog. I am officially in my last year of high school! It’s a strange feeling knowing that this is my last September, that the little me in 6th grade, who acted out because she found things too easy, now struggles to showcase her learning.

This blog post is going to take us through my most recent humanities project, but I am going to start elsewhere. You might be confused at first, I promise that it’s all connected. Let’s get into it!

I have always been told that I’m smart, but that I need to apply my learning better. Throughout the last few years, this has been a prominent issue in my learning. I find that I am always trying to do more, and in that attempt, I lose the ability to do any of those things in depth. I was under the impression that the day that I chose to do less would be the day that I would gain that depth back.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t the case. This year, I cut back on the amount of hours I was spending on gymnastics and my job. Instead of training 16 hours a week, I’m now doing 12. Instead of working 8 hours a week, I’m working 4. So, technically, I should have 8 more hours to do homework, process my life, and maybe even have social interactions with people.

This year, I began with the intention to fully reach towards extending my learning, in a way that I never have before. Based on the feedback that I’ve spent my whole life receiving, I feel as though this is completely and totally in my reach, and just what I need in order to continue challenging myself throughout the remainder of my high school experience.

Over the course of this past project, I have learned that this simple recipe for extending my learning (decluttering my brain; giving myself space and time to make original connections to my learning) won’t necessarily give me what I want. It’s an especially frustrating feeling when I reflect on how the entire reason I decided to start in PLP, all the way back in grade 8, was because I wanted to extend my learning – not necessarily in my grades, though I assumed (hoped) that they would come with it, but in the knowledge I would gain. All I ever wanted was to learn more about the world around me. However, even if the grades I was rewarded with weren’t necessarily where I was shooting, I am extremely proud of the work I’ve done in this project. Even if it was not extending based on the proficiency scale given to us for school, on my own personal scale for my own learning, I feel as though I was moving further past where I have ever gone before.

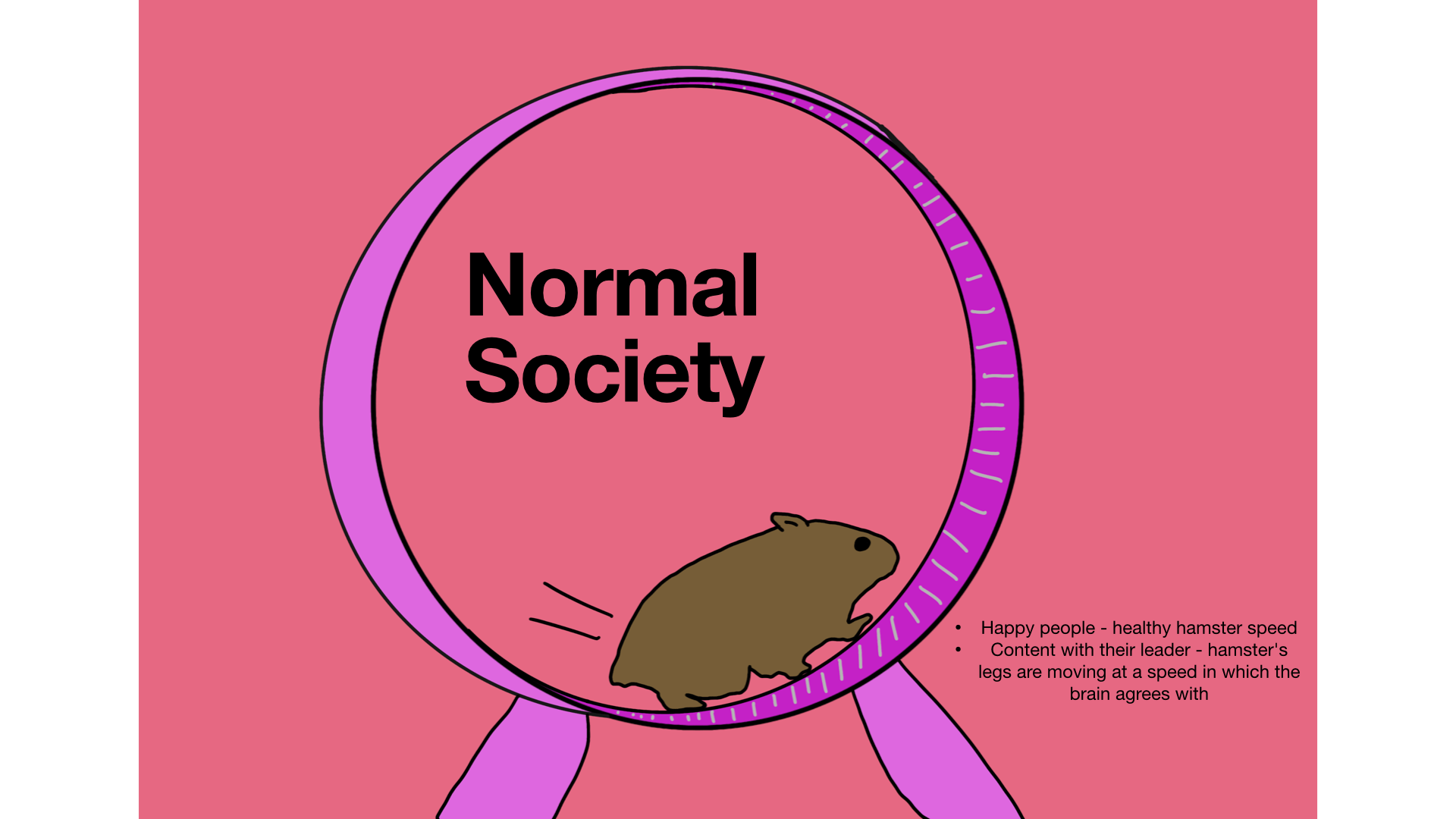

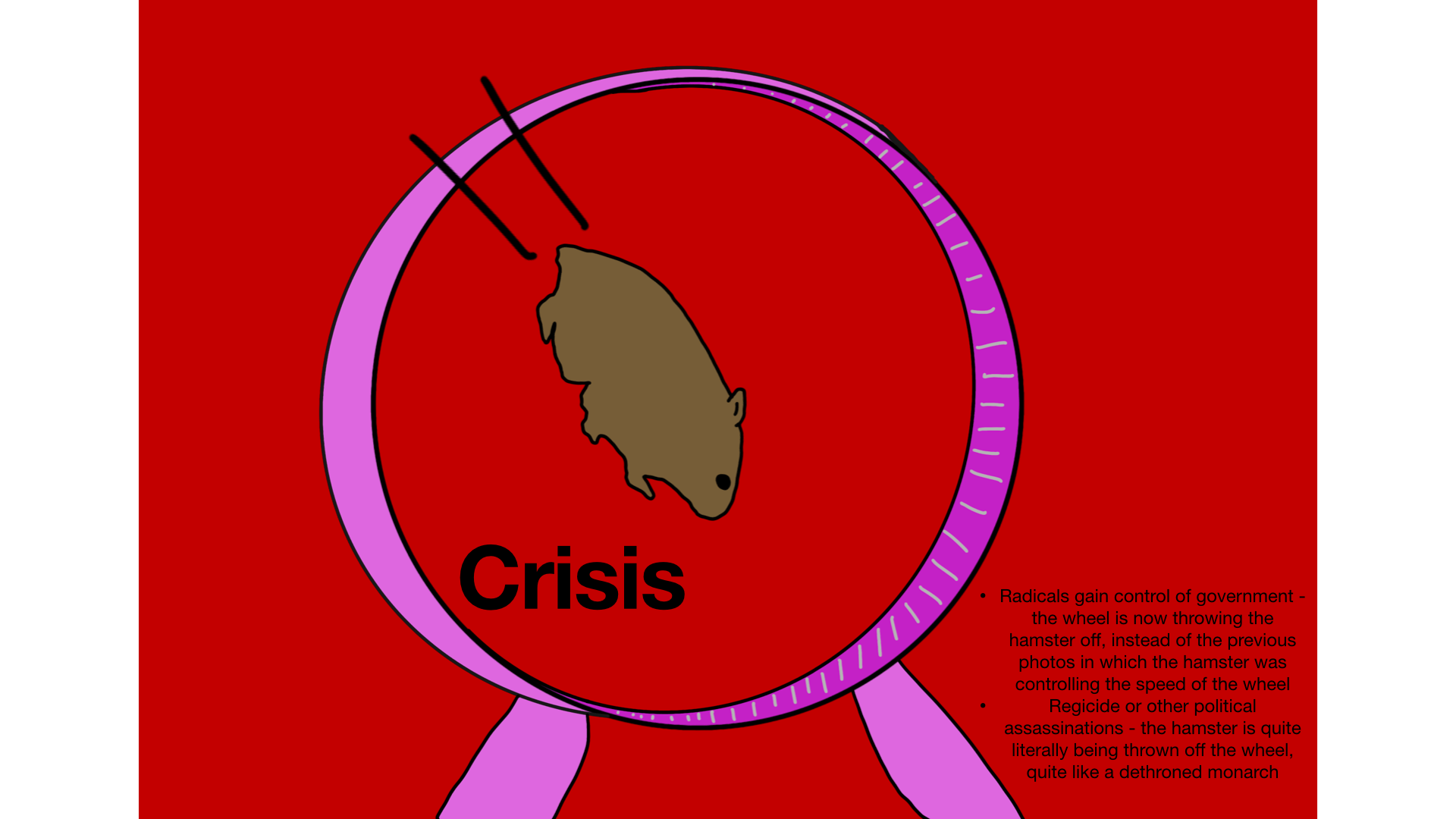

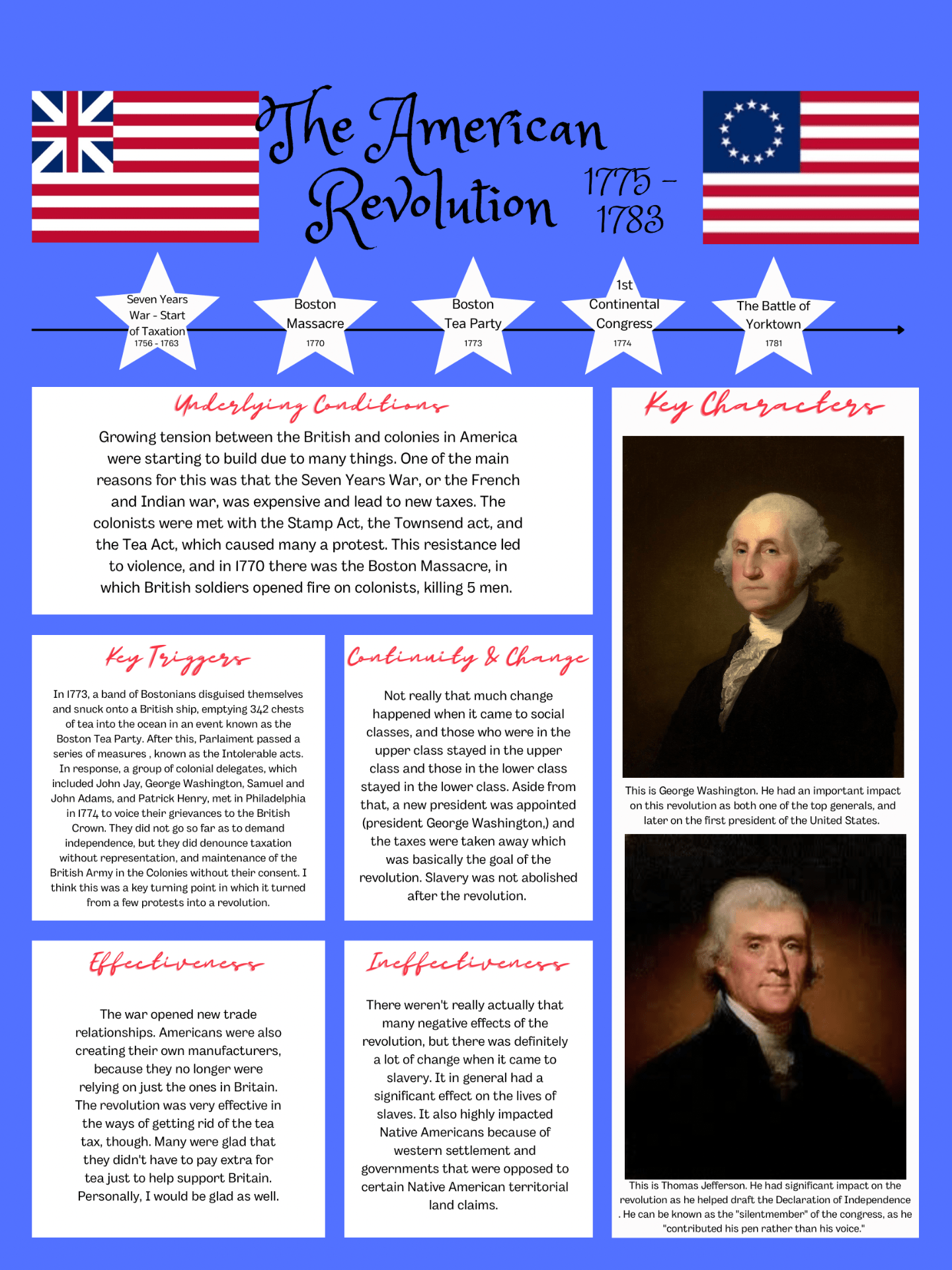

The project I am talking about was called “Don’t Be Dic-tator,” in which we took a deep dive into the signs of rising authoritarianism and a very current risk of dictatorship. We used Timothy Snyder’s book, On Tyranny, as a main resource (which I urge you to look at – it was a brilliant read), and also looked at a few case studies on historically significant examples of authoritarian dictators. By the time we had completed that, we had built sufficient knowledge to begin working on our end product: a 25-minute documentary explaining the warning signs and potential ways to fight back against authoritarianism. All 17 of us PLP 12’s worked collaboratively on this documentary, splitting it into 4 different segments that we decided were significant to touch on. Once it is released, you can find our documentary linked here.

My proudest moment within this project was probably the first benchmark, which was a literature note and two permanent notes to add to my Zettelkasten talking about my main takeaways from On Tyranny. Now, as I mentioned earlier, I was absolutely enthralled by this book. It brought up so many different perspectives that I had barely even considered before. For example, in the prologue, Snyder mentions how when America gained independence, they were trying especially hard to avoid a single individual or group seizing power for their own benefit. He goes on to explain that because this is such a prominent idea in the USA (because this idea of freedom and equality is placed upon a pedestal as if it’s a trophy and not just the bare minimum), a major topic of political debate is tyranny found within smaller niches of society (scaled down into smaller communities or groups). An example he gives is women and how they often get treated in domestic abuse situations – how the abuser has all power over her and her body, how they might be the tyrant of the nation that is a woman. When I first read this passage, I was amazed by this idea. As I continued to read the book, I continued to be fed these thoughts that I had never even considered before. Again, Snyder’s work absolutely fascinated me, and I would highly recommend looking into his work for yourself.

Once I had finished reading the book and taking all my notes on it (and wow, I had a lot of notes. There were so many things to take away!), I added an extra little reflection on many of the little connections I had made to my life while reading this book. This never-ending train of thought is probably one of the pieces of work that I am most proud of from all of my time in high school so far – not because it might be what is important or useful for this project, but because it came so easily. I had so many things to say that were so interesting to me – so many thoughts that came in an endless stream straight out of my brain.

I began this reflection with a takeaway that I feel is an important way to look at our lives right now: “Not everyone has the freedoms to choose many things, but we all as people get to choose how we react to things in our lives, and those choices in turn change the course of others’ lives. Together, these choices make up the mosaic that will one day be our history.”

I went on to talk about the thing the has caught my attention the most throughout this project: at the end of the day, all of these historically horrific authoritarian dictators were humans, too. They were born, as we were, and lived, as we do. At some point in their lives, something went wrong and they ended up where they did, instead of where we are. Somewhere within a collection of moments, something bad happened and they chose the wrong way to react. As I learned about these dictators (Hitler, Mussolini, Saddam Hussein, Pol Pot, etc.) I could see myself in them, which may seem strange, but I’ll explain.

When I was younger, I would tell everyone “I’m going to be the first female prime minister of Canada!” I wanted to do it better, to fix every facet of society, to be written in history. (I wanted, I wanted, I wanted.) This was not fully born from ego, although there was a bit of that in the mix too (a small part of me that wanted to prove that I could be good at things, just like the other kids, if I actually tried for once. What I didn’t realize was that trying looks different on every child, and for the most part, I was trying – it just looked different from the kids who sat up straight and raised their hands to speak and followed the exact checklist for what the teachers wanted). The main source of my want was simply out of anger – at its core, for me, it was directed towards the education system. But I thought bigger picture – so I redirected it to the government, broadening my anger to many different areas of society. I wanted nothing more than proof that there could be a better version; that there must be an easy fix; that there could be a perfect world. As I grew older, I realized that it simply wasn’t that easy. By the time I got to 7th grade, my vision had narrowed once again, into anger at the education system. “I’m going to be the first female prime minister of Canada” had turned into “I’m going to become the superintendent”. Eventually, I realized that, too, was ridiculous: there is no “easy fix”, otherwise it would have already been done.

You can see the similarities in this train of thought to those of an authoritarian dictator (of course, we don’t know exactly what any of them were thinking, for we are not them, but we can begin to infer based on the actions they chose to take.) I liked to believe that when all of them seized power, it was out of a drive to make a nation better, and they just went about it the wrong way. But at the end of the day, in my childish train of thought (the one that had me believing that I would be able to run a nation if I just tried for once) it wasn’t solely about me being the one to swoop in and fix things (although the idea of proving everyone who hadn’t believed in me wrong was quite appealing). It was about someone, anyone, fixing the issues deeply rooted within our society today.

Through much more reflecting, and one long conversation with Ms. Madsen, I reached a seemingly hollow conclusion to the question that had been nagging me for the entire project: “what exactly draws the line between a child like me and an authoritarian dictator?” The answer was simply narcissism. Once I reached this conclusion, I felt a little (maybe more than a little) frustrated. I felt cheated, as though this question deserved a larger answer than what I had found for it. But as I thought about it more and more, asking myself more questions by extension, I realized that this one-word answer held more than it gave credit for.

Going back to the comparison between myself and many historical dictators, as I grew older, I had the privilege of being taught that there is not, in fact, anything within me that makes me special, that makes me better than everyone else. Some people do not have that privilege, and as they grow older, they just get pushed up onto higher and higher pedestals, without one single thing damaging their egos (and we all know this is much more common among men: hence the fact that every dictator that we looked at was a man). By extension, some people are just born with more narcissistic tendencies than others: potentially leading them to think that they would be able to manage an entire nation and serve it well, all on their own.

This opens up the age-old question: nature vs nurture: Are power-hungry, dictatorial tendencies taught? Or are some people simply born like that? Was I born like that, and simply taught out of it? How much can we change with how we raise a person? Are there traits that simply cannot be taught out of a person, no matter what is done? And this reminds me of a thought I once had, long ago, just after I had realized that maybe being the superintendent of our school district was not, in fact, my calling: if I had a different name, would I have a different personality?

These are many questions, all directly related to one another (though the one about my name might be further off, but still relevant). However, one is, in my opinion, the most relevant, as it gives us the most evidence towards figuring out why these dictators chose to react to a crumbling nation in the way they did, instead of continuing to grow older and wiser and helping in the smaller ways that a citizen might be able to (because at the end of the day, it’s the population who holds the most power – another major takeaway from On Tyranny, but one that I am simply less focused on). Was I born with dictatorial tendencies, and just taught out of it? We can attempt to find the answer if we circle back to nature vs nurture in personality development, and through a bit of research, I found that we won’t be able to find a concrete answer, because there is none – every situation is different, and a person and every inch of their being is built on a foundation of a complex weaving and intertwining of nature and nurture; of the way they were born and the experiences they have touched in between that and death. Studies show that people are predisposed to have different personality traits genetically. However, people change as they grow up and grow old. Personally, the conclusion I have reached through this is that we are all born with deeply rooted traits (for me, that probably contained the need to prove myself, as it probably did for most of the dictators filling our history. Although, even that was probably fed by the way that I felt as I developed: as though people didn’t believe I could do many good things), and as time passes, as life moves, many of these traits ebb and flow; new ones develop; old ones get lost. But the ones rooted deeply within us (for me, the need to prove people wrong about me) are hard to budge: not impossible (I no longer think that I could fix the world on my own, or at all, in fact, because really there is no perfect fix), but definitely difficult to uproot.

Through this, I have realized that this version of myself as a child was not necessarily a pathway to tyranny, though it certainly could lead there. Somewhere within, there was a crossroads, and the true and complete definition shows us the exact different between tyranny and ambition. And through all this thought, I have come to the realization that the true distinction between these two very similar traits is narcissism and humility.

So, to restate the question: what exactly draws the line between a child such as myself, and an authoritarian dictator? The answer lies in the narcissism deeply rooted within one’s tendencies, and whether it can be untaught. A child (in most cases) can be taught not to operate with such a high ego. They can learn that there is more to life than just themself and others’ opinions on them. An authoritarian dictator is a person who was never untaught these ideals. Someone who believes that they can fix it all. Even when the intentions are positive, this narcissism leads them astray, and in the end, many people get hurt.

When writing this post, I only intended to showcase the process that brought me to that conclusion. However, reading back on it, I am realizing that I took a major step in finding the solution to my one other main question: together, can we create a world where no one ends up on the pathway to becoming a dictator?

The answer, at its core, is no. There is no perfect world, where no one holds those tendencies. However, we can begin to constantly work towards it, for however close we can get is better than not trying. To achieve this, we must all work together, especially parents and teachers. We must snip it at its root – unteach narcissism, and teach children to be humble and strong (the two do not have to contradict, in fact they often work hand-in-hand). Together, we can work towards a better world.

My notes on the book (and personal reflection, at the bottom) can be found here.

This project took me through a journey of finding the answer to this question: a rather fantastical journey, if you ask me, for I have never looked so deeply within myself for a history class before. It fills me with joy to know that I truly am learning things in school (about myself, about the world) – which is something that I yearned so completely for when I was in the 7th grade.

Thank you for journeying through it with me. It’s been a wild ride, and I am so excited for the next project. See you soon!