Revolutions on trial, the project in which we argue about revolutions to see if they accomplished their goal or if it was completely pointless waste of time. But before we get to that, we first need to understand what a revolution actually is and why they happen. We started this by literally staging our own revolution.

Nation X was a role playing game that we played at the start of this project. In it there were 4 different groups, A,B,C,D. Each groups had wildly different levels of freedom and power. Groups C and D were the wealthy and powerful, while A and B were the poor working class. After everybody established which group they were in, we were told to create a free and fair society and could do pretty much whatever you want to get there. Of course what actually happened in a big class of grade 9s was complete chaos. Groups A and B staged a storm of the capital that was stomped down, everybody was trying to stab each other in the back, and eventually I made agreements with all groups and created the first constitution to hopefully push the society in the right direction.

Even though this was a complete mess and nobody really knew what was going on I did learn a few valuable things.

1 – Revolutions are super confusing and nobody really knows what’s going on.

2 – Revolutions commonly occur when there is mass internal conflict and conflicting ideals.

3 – Revolutions are not always successful, and can easily fly off the rails.

You can also read my reflection on it for more detail into what happened.

After planting the seeds of a revolution in our heads, we set out learning about why revolutions happen.

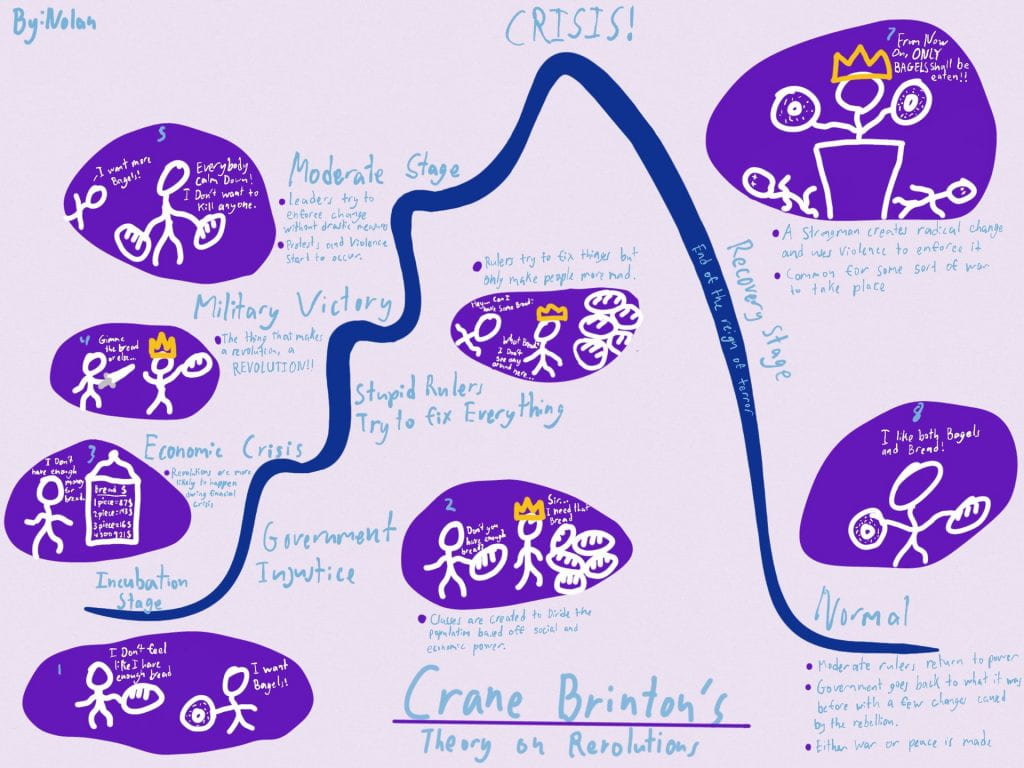

Animal Farm is a short novel written by George Orwell and based on the Russian revolution. Throughout the book, we would have book discussions, as well as compare it to the other thing we were learning about, Crane Briton’s theory on why revolutions happen.

In the end we wrote a in class multi-paragraph essay about the anatomy of the animal revolution through the use of Crane Brinton’s theory. I hate doing these because my brain always becomes scrambled eggs trying to think that fast. Although this one ended up going pretty well and I’m considerably more happy then the last one I did as a result.

The Anatomy of the Animal Farm Revolution

Once we learned why a revolution happens, we started to learn about the real deal. I was put in the Haitian revolution group, a revolution that I had never heard about prior to this project. Turns out that revolutions are extremely complicated and confusing, especially the revolution that I was assigned.

A very quick summary of what happened, Saint Domingue (what is now the country of Haiti), was ruled by the French, but populated largely by the enslaved population. The enslaved population, not wanting to be enslaved for the terrible conditions they had to endure and sensing that the time was right, decided to revolt. 13 years of fighting later that included lots of betrayal, alliances, more betrayal and heavy loss of life, the enslaved population came out victorious and declared the nation independent as well as forever abolishing slavery in their new country.

[I’ll link some informative videos if you want to learn more about it.]

By the end of this process I feel that I had a pretty good understanding of the revolution. I tried my best to find the truth out of all the contradicting evidence and went through lots of different sources to fully flesh out my knowledge which can be seen in my four full pages of notes that I ended up with. These notes however had a big problem. They were almost impossible to navigate. I first started taking notes by source, which wasn’t terrible but had the side affect of repeating information which was a big waste of time. I eventually decided to organize them chronologically based on the revolution. This it turned out was a huge mistake as after I was finished, I was greeted with a huge block of text. This made it almost impossible to find where stuff was, and also what source it came from which made fact checking way harder then it should have been. I think I’ve talked about this problem in a previous post, and honestly I’ve completely failed again at it. Hopefully I can figure out a good strategy for this in the future because this won’t be the last time I have to take notes on a big topic.

Thankfully we also created a graphic organizer, which is much better organized and condensed compared to my notes, while still keeping most of the big ideas.

After learning everything we could about our revolutions, we were separated into two teams. One team would be the defence and argue that the revolution was effective and the other would be the prosecution and argue that it was ineffective. You may have noticed already, but this is exactly how a real court would do it, and that’s because we were about to become lawyers, and argue our cases at the winter exhibition. Sounds fun right? Oh sorry, I forgot to mention that presenting a the winter exhibition also means in front of a live audience of which would also be the jury and decide whether or not the revolution was guilty or not guilty. I am definitely not nervous at all.

We immediately started working on our case. I was put in the defence team for this case consisting of Teva, Ewan, Gabi, Xander, and myself. The first thing we did was create an affidavit, in which we put all of our sources that we were going to use in our argument. I decided to put in some of the constitutions that were created at the time, since it showed how the laws changed from ‘the enslaved population may be punished whenever’ and more towards ‘Slavery is forever abolished and everybody is equal.’ I also added our one secondary source, and if I were to do it again, would probably add more of the them since it’s always good to have more information. By the end we had an affidavit full of sources, now we just had to figure out how to use them in our case. To do this we created a bunch of questions that we would ask both our witness and their witness. These questions were the hardest part of the project. Trying to create questions that compel the witness into saying what you want is not easy, and all of our questions went through many revisions before we finalized them.

After our questions, we started on our script for the show which turned out to be a complete and utter mess. Everything was constantly changing, from lines to questions to entire characters, all in the name of trying to make the script and our arguments as good as possible. Honestly the coolest part about it was seeing how devoted people were, with a lot of people sacrificing their free time to work on it. In the end we finalized the script with a little over 24 hours before we would perform, which also meant that I had only one day to memorize all my lines. Yay! Overall I’m quite proud of the script. Is it perfect? Absolutely not. To be honest it’s a bit boring, hard to follow and both arguments could still use a bit of work. However the amount of work and improvements that were made to it from both sides in the days leading up to the trial was really cool to see.

Thankfully at the event, everything went pretty smoothly. I only had to remind myself of a line once and everybody else did a good job as well. (I may have also spelt my last name wrong but we don’t talk about that.)

You can watch the entire event here:

As well as the other revolution trials:

At the end of the trial the audience (they were the jury) would decide if the revolution was guilty (ineffective) or Not Guilty (effective) based off the 6 criteria that our class agreed on

Our 6 Criteria for a effective revolution:

1. Political reform aligning with the voice of the people

2. Increased rights, freedoms, and liberties for the people (religion, mobility, speech)

3. Removal of dictator with sweeping powers

4. Financial stability achieved (jobs, industry)

5. Standard of living improved (food, shelter, water)

6. Removal of internal conflict

In our case, after much deliberation from the jury, they went with the verdict of Guilty. I’m not mad about this as the vote was very close and the other team worked really hard on improving their argument in the last few days.

So what did I learn, well I’ve always viewed revolutions as the big points in history where everybody bands together to create changes for the better, which is only half correct. As explained in Crane Brinton’s theory on why revolution happens. In the Incubation stage, the revolution starts with a common goal or a set of ideals. But by the end of the revolution, a lot of the main goals of the revolution are lost with only a few key points making long-lasting change while everything else goes back to the way it is. Sometimes the key change is something big like how the Haitian Revolution started the abolishment of slavery across the world while in others literally nothing changes except for having a leader with a different name.

Now for the driving question, how can we, as legal teams, determine the effectiveness of a revolution? Well, as shown, we can determine the effectiveness of a revolution by researching and presenting cases in front of a jury who could then decide for us. However the thing I found most interesting was determining what actually makes a revolution effective. For example, the Haitian revolution wasn’t that effective for the inhabitants of the island, but for the rest of the world it had huge impacts. Therefore should we consider the revolution as effective or ineffective? Maybe we need another trial to figure it out.

Anyways thanks for reading this very long post. This project was quite interesting and I had a lot to talk about.

See you next time,

Nolan 🧑⚖️